Nobody Puts Baby in the Corner

Judith Butler didn’t invent gender ideology, anthropologists did.

Both critics and enthusiasts of gender theory invoke Judith Butler’s 1990 book Gender Trouble as a foundational text. My admittedly peculiar aim in what follows is to establish my own discipline’s prior claim to a body of theory I dislike intensely. Whenever credit or blame is apportioned for gender ideology, that’s me in the corner of the ubiquitous party meme.

Well, no more. I’m going to shake what my grad program gave me by going through a rather obscure 1981 article by Marilyn Strathern: Dame of the British Empire, Fellow of the British Academy, emeritus professor of anthropology at Cambridge University. Strathern is renowned among socio-cultural anthropologists but almost unknown outside the discipline. Alongside the rather more famous (but still less famous than Judith Butler) Donna Haraway, Strathern is one of two senior “feminist anthropologists” who have carved out splendidly successful professional careers built in considerable part on attacking feminist work. Strathern was born in 1941 and Haraway in 1944. Judith Butler (born 1956) pulled a typical Boomer move by stealing the public spotlight from these two older members of the Silent Generation.

Haraway, emeritus professor of the History of Consciousness at UC Santa Cruz is a subject in her own right. I’ve discussed her here and Jane Clare Jones is very good on her here. Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”, which articulates many key themes of gender ideology, was first published in 1985, predating Gender Trouble by five years.

Even earlier, however, is Strathern’s 1981 article “Culture in a netbag: the manufacture of a subdiscipline in anthropology”. “Culture in a netbag” allows us to spot in the wild a series of now-thoroughly domesticated assertions, chief among them that there is “No such thing as woman” (the header to the concluding portion of Strathern’s essay). Like Judith Butler, Marilyn Strathern is notorious for a prose style that is frequently impenetrable. This characteristic is already well developed in the 1981 piece, but Strathern is nevertheless plainspoken about what motivated its writing. The first line of the article abstract refers to the “straw man of male bias which informs much feminist-inspired anthropology”. Halfway through the essay, the penny drops: “I myself become one of Weiner’s straw men among those castigated for propagating a male view of the society studied… I fall into the ‘traditional male trap’ of not taking women’s exchanges seriously.” (672). Strathern’s argument is an early pearl assembled around the grating irritation of scholarship that pays attention to women.

It is significant that Weiner was slightly older than Strathern: born in 1933, Annette Weiner died of cancer in 1997. Weiner participated in a florescence of feminist scholarship built up between the 1950s and 1970s that was systematically beaten back during the 1980s. Anthropologists do recognize a disciplinary backlash to feminism during this period, but they lay it entirely at the feet of straightforward misogynists like Napoleon Chagnon working in the paradigm of sociobiology (later called evolutionary psychology).

To use a clichéd phrase, that’s not the half of it. Strathern and Haraway were also key early figures in the counter-revolution. Judith Butler was a later arrival to a wildly successful and still-ongoing campaign of virulent anti-feminist backlash in academia. Interestingly, the evolutionary psychology part of the backlash – though launched in overt hostility – has undergone a feminist counter-counter-revolution in the years since. The role of women in the human story is now at the heart of emergent work in evolutionary psychology. Meanwhile, avowedly “feminist” anthropological work in the Strathern/Haraway vein continues ever more fervidly to insist that not only do women not exist, humans are contingent part-microbial, part-animal, part-mechanical, part-AI assemblages who aren’t looking too solid either. Feminists are not wrong to say the diminishment of women undermines humanity generally, wherever it happens: in everyday practice or in intellectual discourse.

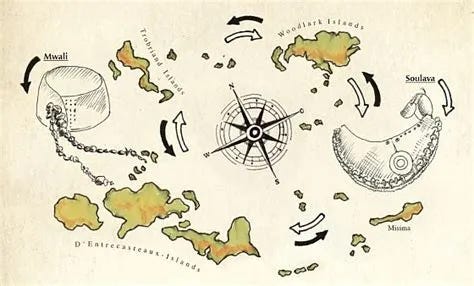

The original form of Strathern’s article was delivered on November 3, 1980 as the “Malinowski Memorial Lecture” to honor Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942). Malinowski is a foundational figure in anthropology and wrote one of its most lastingly famous ethnographies: Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922). The Argonauts demonstrated the powerful results obtainable through a then-new research method – participant observation – which has since become the core of anthropological practice. Malinowski offered a fascinating account of the “kula ring”: a linked network of inter-island voyages via sea canoe undertaken by Trobriand men to exchange regalia made of shells. Necklaces are transacted in one direction, arm bands in the other, in a never-ending cycle of ongoing trade which is a key means by which Trobriand men can aspire to, and in some cases attain, wide social prestige.

The first portion of Strathern’s lecture posits that it was a habit of Malinowski’s to make “straw men” of the ideas he set out to disprove with his own work. Strathern argues for Malinowski having been something of a confidence man: the more successfully he could manage to portray a bias he opposed as being universally held, the more “a comparable universalism attache[d] itself to the substituting proposition” (667). For example, when Malinowski set up a proposition like “the economic life of savages is simple and exclusively pragmatic” only to knock it down by showing “the Trobrianders whom I study engage in elaborate ceremonial exchanges”, he meant to assert not just a fact about Trobrianders but also to make a new kind of universal claim about “savages” in general (which, in the parlance of his era, meant “traditional humans”).

If it seems odd that Strathern opens her “Malinowski Memorial Lecture” with a rather less than flattering take on the eponymous man of honor, it will help to know that by 1980 it was quite a widely held view among anthropologists that Malinowski was a remarkable fieldworker but an inadequate theorist. Admirable as a methodological pioneer, but not really an intellectual heavyweight. In truth, for all its vaunted commitment to “the field”, anthropology has always preferred a library man to a fieldworker. It would not therefore have shocked anyone in the audience to hear Malinowski spoken of deprecatingly. Pooh-poohing him would not have made for an at all original contribution on such a prestigious occasion, nor was that Strathern’s real aim. Strathern turns Malinowski’s diminished standing in the disciplinary pantheon as a practical innovator but intellectual rather dim bulb to a more proximate use. Malinowski provides the convenient scarecrow suit into which Strathern will spend the rest of the lecture stuffing feminist scholarship, women’s studies, and – most determinedly – the fellow Melanesianist who had so recently accused Strathern of “propagating a male view”: Annette Weiner.

In 1976, Annette Weiner had published a widely hailed re-analysis of Malinowski’s Trobriand ethnography. In Women of Value, Men of Renown: New Perspectives in Trobriand Exchange, Weiner showed two things. First, that Malinowski had only mentioned in passing but not paid proper attention to a form of elaborate ceremonial exchange operative among Trobriand women. During mortuary rituals, Trobriand women distribute woven banana leaf bundles to pay off the “debts” of the deceased. Thousands of such bundles are prepared and distributed, particularly if the deceased was a prominent person. These exchanges make tangible the relationships among people and also the relative importance of different community members. Second, Weiner argued that Malinowski misrepresented just how unequal kula outcomes tend to be. While, potentially, any man may become “famous” in the kula trade, in practice a very few men dominate the acquisition and transaction of high-status regalia and most men never come near to possession of any celebrated named shell (the dream of all kula “players”) during their lifetimes. Weiner, then, was interested in both women and in men, and she was interested in how social hierarchy is established among them.

Weiner demonstrated that there was both a symbolic and practical intercalation of the soft wealth of women and the hard wealth of men, that men’s inter-island “fame” was linked to local relationships marked and maintained through women, and that success in the inter-island traffic of literally hard, durable worldly goods meant for lively, showy display was grounded in the circulation of women’s soft, perishable, continually remade woven goods brought out locally at life-marking events: mortuary rituals and marriage exchanges. These woven goods, made and remade by women, were symbolically associated with women’s fertility: that is, the power of Trobriand women to produce new Trobriand people (who, in Trobriand understanding, are themselves continually “recycled”). It was a dazzling book, and an unsentimental one. It explained how the symbolic capture of women’s fertility was crucial to the construction of social hierarchy among both women and men: a theme Weiner expands upon in her utterly brilliant 1992 work, Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-While-Giving.

To return to the 1980 scene, however. The rhetorical set-up of Strathern’s essay is both clever and nasty. She opens with what is by 1980 a widely-held anthropological take on Malinowski: an innovator to whom we all owe a debt of disciplinary gratitude, to be sure, but a ham-fisted thinker and a tricksy rhetorician with an ambitious eye for the main chance. Malinowski used “straw men” as a means of scholarly self-promotion, to make his work seem more important and original than it really was. Given that his legerdemain was key to making a place for anthropology in the academy, it’s right that we should annually show ourselves grateful to him. But really, only for his innovations of method: hardly for his intellectual sophistication (perish the thought). In an interview she gave in 1996, the year before Annette Weiner died, Strathern emphasized a kindred gratitude to Weiner (2014: 273). Not for Weiner’s contributions to general anthropological theory, oh dear, no: gratitude for what Weiner taught Strathern about a plucky little body of work that, after all, everyone does recognize has its place. A humble little place with a faint whiff of the ersatz about it, as captured in Strathern’s subtitle: “the manufacture of a subdiscipline in anthropology”.

Manufacture

Leaving Malinowski behind, Strathern helpfully moves on to the “manufacturing” process she wants her audience to understand. Just as Malinowski (that canny old dear) maneuvered to ensure that “Anthropology as a science was to be built up in the face of prejudice”,

“the new anthropology of women retakes this methodological premiss, utilising as its straw man the anthropologist suffering from male bias” (667).

In other words, Strathern is telling her audience, those pesky little Weiners that have been springing up in our discipline are hardly so original as they pretend. In fact there is no end to their derivative chicanery: “The second Malinowskian characteristic is the universalizing mode, one of the straw man’s tricks” (667). Strathern elaborates:

“The new appraisal casts out the old as a world view – and manages to suggest that in its place is a freshly conceived view of the total world. Hence, the claim may be made that we have been ignoring a significant universal, the category ‘woman’… it is a persistent premiss… that there is a social category whose dimensions are knowable on a priori grounds such that studies of particular women exemplify attributes of a universal womankind” (668)

At the end of this section (titled “Straw men” in case anyone missed the point) Strathern sticks in the knife. The women working in this manufactured sub-discipline are so deluded as to reveal a knuckle-dragging, mouth-breathing, sub-Malinowskian level of perspicacity:

“Malinowski never pretended he was a Trobriander… Malinowski put forward the Trobriand view as replacing uninformed western bias about Primitive Man. But if Malinowski also saw himself as the cultured author of this view, some women’s writings give the impression that in their case the continuities between author and subject of study are ‘naturally’ grounded” (668-669).

All of this in 1981 (published version), and only three pages in! Here we see already all of the postures and postulates of gender ideology, fully formed at a time when Judith Butler was still a wet behind the ears 25 year old grad student. The patronizing shake of the head at anyone so naïve as to suppose there might be a continuity based in (scare quotes) “nature” among women. The condescending dismissal of the proposition that there is a “significant universal, the category ‘woman’”, which has hitherto been ignored in scholarship. Finally, the reassurance offered to Strathern’s fellow scholars that should any of their work look a bit critiquable on feminist grounds, not to worry: such critique has been “manufactured” in bad faith, is unoriginal, and terribly dim-witted to boot. It’s perhaps not surprising Strathern was so quick to spot personal ambition tucked away within Malinowski’s professional rhetoric. Telling, in 1980, an at the time overwhelmingly male audience that all this recent hullabaloo about women wasn’t anything to take seriously was an outstanding career move for Dr. (now Dame) Marilyn Strathern. To do this and call it feminism: well, if Malinowski’s ghost was in the audience he must have whistled in admiration at the sheer, careerist cheek.

Subdiscipline

Radical feminists have long noted that women’s studies has been defanged by being transformed, as it has been almost everywhere, into gender studies. Particularly in anthropology – for many years unsubtly glossed as “The Study of Man” (the premier English and French anthropology journals were long titled Man and L’Homme , respectively (Man is now the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute; L’Homme has not changed its name) – attention to “Woman” was genuinely revolutionary. A major task of Strathern’s 1981 essay is to cut this attention to women back down to size:

“The endeavour may be towards a complete reorientation of the whole discipline… Methodologically the result is a “subdisipline” [my term], although to its practitioners it may also be a metonym for an entire reinvented anthropology” (669).

Strathern here emphasizes that (like Malinowski) feminist anthropologists are innovative only in the arena of method (paying attention to women’s activities), and there only to the degree of creating a “subdiscipline” – whatever “its practitioners” imagine about it. She concedes that straw men are not all bad in that they can be “energising” (670), but “it is their further tendency to promote a misplaced universalism that is not entirely a good thing”. It is fine and interesting for feminist anthropologist to pay attention to women’s activities; what they must not additionally do is claim that “Particular studies can thus yield universals about the condition of womankind as such” (670). In other words: it is in their ambition that feminist scholars go awry, in their unwarranted “supposition that the new perspective bears a closer correspondence to reality” (671). Women anthropologists paying attention to women’s lives have gotten the idea in their heads that their efforts make anthropological work more realistic and thus more scientific, but pshaw: they are just wrong.

Why has the mean-spirited misogyny of this argument been missed? How has the scholar who made it come to be hailed as a leading light of “feminist anthropology”? This is an argument that attention to women’s lives only enables small (“subdisciplinary”) claims, and that within anthropology attention to women certainly does not yield a “closer correspondence to reality”: that is, a clearer and more thorough understanding of the human story as a whole.

If you are among those unrepentant feminists who think male bias is a real problem and not just a straw man, it may be obvious to you why proffering arguments like was great for Marilyn Strathern’s career. What nevertheless needs explaining is how she could make an argument like this and be famous in the discipline as a *feminist* rather than as a reactionary. Here again, the tricksy bad faith Strathern strategically attributes to Malinowski is revelatory about her own scholarly practice. The more she can attribute smallminded stupidity to researchers interested in women, the more she can claim broad intellectual rigor for whatever she substitutes in its place. What she substitutes is, of course, “gender”.

Gender

Weiner had faulted Strathern for not paying attention to the exchange of netbags among women in the society (Hagen) of the New Guinea Highlands where Strathern carried out her fieldwork. To counter this criticism, Strathern compares the role played by women in Hagen exchange to that played by women in another Highland New Guinea society: the Wiru (drawing upon the work of her then-husband, Andrew Strathern). Strathern argues that women’s roles in exchange are so different in these two Highland New Guinea societies that it is impossible that there could be anything unitary about “womanness” even in this one remote corner of the world: let alone, mutatis mutandis, across human experience generally. As she has it: “Neither the attributes associated with womanness nor the technical processes of symbolization are the same” (677).

Here Strathern brings in a myth from a third society, that of the coastal New Guinean Orokaiva, about men and women exchanging gifts of palm and coconut. She gives a baffling (anachronistically, one might call it Butlerian) gloss of the myth expressed in terms of exchange, maleness and femaleness, metaphor and metonymy. You must simply take her word for it that hers is a convincing take because she does not recount the actual Orokaiva myth in any way. The upshot is as follows:

“These procedures are found side by side within the one Orokaiva myth. I lift them out of context and suggest that in constructing wommanness in relation to manness Wiru employ the logic of metaphor, Hageners the logic of metonymy. In other words, there is a fundamental contrast between these two cultures in the very manner in which symbols are generated out of gender” (678; emphasis mine).

All is made clear on the next page:

“In cross-sex exchanges gifts thus take one of two forms. Either women contribute women’s things and men men’s things to each other’s endeavours; or else men and women are mediated by a gift such as pig not itself given gender. However they are structured in other contexts, symbols that bring the sexes into conjunction turn or relations between differences and employ the logic of metonymy: each sex transacts with part of itself, with a nature constructed in a prior manner and not to be reconstructed in the transaction itself. Wiru is very different” (679)

Different than what again? Well, don’t worry about it, let’s just move on to the Wiru case and maybe that will help us figure it out:

“Wommanness in Wiru is thus self-signifying, as a metaphor is self-signifying (Wagner 1978b: 76; pers. comm.) Womanness is valued as reproduction, manifested in its own products. Aspects of parenthood are certainly differentiated by gender; yet through time this difference is annihilated. … Indeed, far from the person being differentiated from his maternal origins, he or she is identified with them: these origins are constantly reaffirmed. In one sense the gifts recreate what is already created. Yet in another sense the child which replaces the woman is also more than the woman.” (680)

As with the Orokaiva myth, if you’d like to know more about that personal communication in which Wagner explained to Stathern how exactly “a metaphor is self-signifying” and what on earth that might mean, you are out of luck. But don’t worry, if you didn’t quite follow the argument, Strathern helpfully sums it up as follows:

“Hagen symbolisation constructs the sexes in terms of dialectic and contrast, resolved through opposition or complementarity; Wiru employ a self-signifying, metaphorical mode in which the one can collapse or merge into the other.” (681)

I truly do not understand what Strathern means here, and I have read the pages concerned (677-681) several times over in an attempt to do so. However, let me concede that I am perfectly willing to believe Strathern that the relations between men and women are conceived in one way among the Hagen and in a different way among the Wiru, a point to which I will return further on.

The conclusion to Strathern’s essay is titled “No such thing as woman” (682). All of the foregoing considered, “the proper focus for comparative analysis become not women but the values so assigned” (682). To give Strathern her due, in this single clause she stakes out what has since become an incredibly crowded field of scholarship: gender studies. In gender studies, it is not women who are important or interesting it is the *values* assigned to them: the terrain of semiotics, not of the material.

Although Weiner, not Strathern, is not the focus of this (already very long) essay, here it will be clarifying to explain a bit more about Weiner’s analytic project. Strathern is at pains to collapse Weiner and Malinowski into one figure as much as possible: two ethnographers of the Trobriands who were both methodological innovators but no great shakes in the brains department. Carrying out this mission requires Strathern to treat both anthropologists very shabbily, but Weiner especially so. Weiner’s work is of very high intellectual caliber, and its insights rather more lucidly expressed than are Strathern’s.

Women and hierarchy

Strathern in her eagerness to slash away at what she sees as the key category of feminist analysis – womanhood – misses that feminists are simultaneously, and quite as deeply, interested in hierarchy. Strathern insists: look here, the role played by Hagen, Wiru, and Trobriand women in exchange is very different in each case! In addition, the way women and men are conceptualized as relating to one another is also quite different! How then can we pretend to speak of “women” as a unified category?

First, of course, one notices that Strathern does not suggest her evidence equally dissolves the category of “men”, although even in her abstruse handling it can be gleaned that men play different roles in exchange in the three societies in question and also relate differently to women in each. But that avenue of critique just lands us in the camp of gender ideology via a different route: nothing is anything, men and women are only constructs everywhere, it’s the play of semiosis all the way down. Strathern’s audience in 1980 would not have been ready for that – in fact while Strathern’s lecture made them chortle with satisfaction about uppity women scholars its logical concomitants as applied to the Science of Man tout court would have struck most of them as absurd. In the decades since, many anthropologists have been willing to embrace just such a thoroughgoing decomposition of our subject-matter – humanity – and more’s the pity. But that’s a problem for a different essay (something I’ve attempted here and again here).

The relevant point for present purposes is that feminists are not interested in “women” the way stamp collectors are interested in “stamps”: as a kind of object to be collected in all its variety and pasted into a book. To be a feminist is to be interested in the relationship of women to hierarchy, and it is precisely this relationship that Weiner’s work takes on brilliantly and suggestively. Strathern is quite sure that by showing that not even three kinds of Melanesian women are “the same”, she’s destroyed any possibility “women” can be analyzed in a cross-cultural manner.

The Trobriand Islands and Highland New Guinea are both classed as “Melanesian” societies, but they are in terms of hierarchical social organization very different: Highland New Guinea being relatively more egalitarian while some parts of the Trobriands resemble to some degree the elaborately status-ranked societies of Pacific Islands (Tonga, Samoa, Hawaii) to their east (Papua New Guinea is to the west of the Trobriands). A major focus of Weiner’s 1976 work is the way that hierarchy is more pronounced in one part of the Trobriands – Northern Kiriwina. Northern Kiriwina has more elaborate chiefly lineages, its men are the most successful of all Trobriand men in the Kula trade, and these successful men draw more intensively on women’s wealth in shoring up their chiefly status than do men in other, less hierarchical, parts of the Trobriands.

Now, when Strathern tells us that women’s exchanges and women’s wealth are less important among the Hagen – which is also a less hierarchical society than Trobriand society – this is entirely compatible with Weiner’s analysis, not corrosive of it. I must admit I could not follow Strathern’s respective descriptions of Hagen and Wiru society well enough to understand clearly their relative degrees of social hierarchy. But when Strathern says that among the Hagen there is “no sense in which women’s part in reproduction could stand for social reproduction in general” (683) as Weiner argues occurs during Trobriand exchanges of banana leaf skirts and bundles, Strathern is missing the most critical (and intellectually dazzling) part of Weiner’s argument. It is precisely the way in which the capacity for person-production is alienated and circulated in these ceremonies that serves as a building block for social hierarchy. That a less hierarchical society like that of the Hagen does not get up to this sort of thing is not telling us anything about the artifactual nature of the category “woman” but instead is a piece of data about how different human societies create hierarchy through the cultural manipulation of biological givens.

Every human baby is of woman born but the symbolic expropriation and circulation of the capacity to create new people has been key to the production and elaboration of human social hierarchy. A person for whom many bundles are exchanged at death is in a social sense “more person” than a person for whom fewer are exchanged, although in a biological sense we are just talking about two defunct humans. That Trobrianders have rituals in which women’s capacity to produce new persons is made tangible and literally circulated in physical form is not just a funny little curiosity, but intimately related to the degree of overall hierarchy in that society: including among men. To put it in radical feminist terms, women’s capacity for people production is alienated, expropriated, and circulated in symbolic forms in ways that underpin the establishment of elaborate social hierarchies tout court. The portions of Trobriand society that do this most are the most hierarchical parts and the creation of some people who are “more person” than others has society-wide consequences, such that the men from Northern Kiriwina tend to monopolize the inter-island Kula trade. This is because they can call on more developed and elaborate social networks locally when engaging in it, networks that are only visible to an external analyst who pays attention to women’s bundle exchanges along with paying attention to men’s kula exchanges.

Yes, the less hierarchical societies of Hagen and Wiru don’t have anything like this. This doesn’t tell us there is “no such thing as woman”. It tells us that the relationship between women, men, and hierarchy is different in those places to the way it is in the Trobriands. Weiner went on to study this comparatively throughout all of Oceania, and by 1992 published a magisterial book that analytically connected the egalitarian societies of Australia to the kingships of Hawaii. The production by women of cloth wealth, which has symbolic associations with female fertility, and the circulation of that cloth wealth turns out to be enormously illuminative of regional patterns of relative hierarchy.

Weiner in 1976 published the equivalent of the double helix for feminism: an explanation of how the fundamental building blocks that turn biological sex difference into social hierarchy are scaffolded. Weiner demonstrated that to arrive at this level of analytic insight about human society you have to be willing pay attention to women and their activities at the same time that you pay attention to men and men’s activities. To fail to do this is inevitably to fail as a scientist of humanity. In 1980, Strathern began working furiously to erase the sting of this charge: on her own behalf on behalf of her relieved colleagues.

Not the “queering” of anthropology: the clearing and holding of it for men

Looking at this early piece is clarifying. It shows that the original audience for these arguments -- about how women do not exist, only “gender” does-- was not “queers”. It was men. Specifically, men threatened by and angry about feminist scholarship that paid attention to women and on that basis criticized shortcomings in existing scholarship. What can we make of the fact that it was a woman who was an early articulator of these profoundly misogynist arguments?

Nothing encouraging. Butler was certainly aware of Strathern’s work – in Gender Trouble (1990) she cites the volume Strathern edited with Carole McCormack: Nature, Culture, and Gender. This volume involved another pointed elimination of women, this time written as a riposte to an edited volume published in 1974 by feminist anthropologists: Woman, Culture, and Society. By 1990, however, Butler could draw on a huge body of misogynist “feminist” scholarship in anthropology: Donna Haraway had published her “Cyborg Manifesto” in the mid-1980s, and anthropologist Gayle Rubin had effectively repudiated her own 1975 piece “The Traffic in Women” with “Thinking Sex”, published in 1984. The latter thinks, actually, about gender and is now notorious for its defense of pedophilia: a defense almost exclusively useful to men, as men commit very nearly the entirety of sex crimes generally and sex crimes against children specifically.

What do things look like now in anthropology? The most fashionable new journal of anthropology – Hau- was founded in 2011. It nearly collapsed seven years in following a scandal involving the high-handed treatment of unpaid graduate student interns by its male editor, Giovanni da Col. Anthropology is now a majority-female discipline and this scandal is sometimes described as “anthropology’s MeToo”, although there was no suggestion da Col had behaved in a sexually predatory manner: only that he had emphasized the prestige and networking opportunities offered by unpaid Hau internships both as carrots and (at moments of intense workloads) threats.

In that first 7 years of its existence, here are the stats on the research articles published in Hau’s uber fashionable pages (this listing only counts “research articles”, because Hau publishes work under many other sorts of rubrics which vary from issue to issue: forums, discussions, special sections, and the like). Of 140 research articles published, 98 were by men: 70%, in a discipline that is now 83% female by composition. In 2016, one issue was published in which, unusually, of the three articles in the “research” section, two were by women. One of those two was only two pages long and began as follows:

“I am incredibly intrigued and humbled that Carlos David Londoño Sulkin chose to focus one of three bioethnographic case studies concerning the anthropology of morality on me, my life, and my work. In his very illuminating essay, Carlos underscored what he saw as my strength, or rather my own desire to be a strong African woman. Before reading his article, I would have vehemently denied that I was the least bit a reflection of yet another stereotype of a strong African or black woman. However, Carlos is very much accurate in defining my view of the strength of Kono women—from my mother, aunts, and grandmothers to the Bondo women’s secret society in Sierra Leone—as “savvy resourcefulness” and noting my admiration of such a pragmatic, utilitarian approach to getting one’s way in the world” (2016: 135).

The subject of Professor Londoño Sulkin’s 25 page article? A defense of female genital mutilation, which opened as follows

“I met Fuambai very briefly in 2006, at an American Anthropological Association meeting. I was charmed, finding her charismatic, stylish to the point that I suspected my criteria for judging this were insufficiently sophisticated to do her justice, and beautiful” (2016: 107).

and among other things confidently asserted that the removal of a woman’s clitoris does not negatively impact her capacity to achieve orgasm (ibid: 108).

By my count, Dame Strathern made six appearances in Hau during those first seven years, always in sections organized by invitation. The inaugural issue included a piece by Strathern titled “What is a Parent?”, first written in 1991. Strathern, like Haraway, has since 1990 published extensively (and giddily) on the social impact of new reproductive technologies and how they are reshaping modern kinship. Strathern and Haraway’s work is cited repeatedly in Sophie Lewis’s astonishingly misogynist 2019 book, Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against the Family, which one radical feminist reviewer brilliantly and hilariously summed up as a vision statement for a “Glitter Gilead”. This, then, is feminism as we know it in the highest and most influential circles of anthropology today: all in for defenses of the abuse and exploitation of women, less enthused about publishing them or even recognizing that they exist.

The no-such-thing-as/can't-define-a-woman theorists remind one of Dr Strangelove wrestling with his arm. In every situation, they are able to unerringly identify the thing they repeatedly tell us doesn't exist. Geez, it's almost as if they know exactly what it is. Worse, the non-existence of woman is wholly unlike the non-existence of the toothfairy, unicorns or the planet Vulcan. One can't just prove it and then move on with life. Everyday, in journals, on television, on twitter, in every medium and on every platform, it has to be reformulated and publicly stated. Whole careers---and now industries---need to be built upon it.

This is great, but I want more. A book maybe?